Home/ Blog / Regulatory Reach and – Oops! – Grasp: Part II

One of the cornerstones of the Great Depression-era reform legislation comprising The Banking Act of 1933 was known as Glass-Steagall. The Glass-Steagall Act enshrined a new market principle – i.e., that a barrier must be placed between commercial banking and investment banking. With limited exceptions, these should be separate and distinct activities not to be engaged in simultaneously by a single market participant.

Even though this legislative initiative met stiff resistance during Congressional deliberations of Depression-era reforms – the Great Depression hadn’t completely eviscerated the still powerful banking lobby – the need for such measures was self-evident. One of the major causes of the Great Crash of 1929 was the highly speculative financial activities that retail commercial banks had become engaged in – simply put, commercial banks got into trouble by gambling with their customers’ deposits. So restricting commercial banks from access to more volatile investment banking activities (designated as ‘speculative credit’) was considered a vital aspect – together with the FDIC, federal insurance for account-holders’ deposits – of the reforms minimally necessary to revive America’s moribund economy.

But as the post-Depression decades ticked by, the fundamental utility of this principle gradually faded into the further recesses of the American public’s collective memory. By the 1990’s the prospects of financial reward to be gained from market innovations of the past two generations – primarily but not exclusively relating to derivative instruments – proved too enticing to the now stodgy commercial banks that were hobbled, as they would have it, by such archaic, irrelevant legislative restrictions. This was now the era of Alan Greenspan, the Delphic Oracle of market self-correction.

By 1999, market and legislative consensus – massaged in the preferred direction by the ever-vigilant banking lobby – was that Glass-Steagall was an outdated solution to an outdated problem. We now know better. Thus, the Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act (GLBA) undid those provisions that formed the bulwark of the commercial-investment wall. Sections 16, 20, 21, and 32 of the Glass-Steagall Act were repealed.

It didn’t take another sixty-six years for the results of this change in regulatory architecture to appear. In less than a decade, the imploding pyramid of securitised sub-prime mortgages brought global capital markets to their knees. Just as Napoleon, Adolf Hitler and George W. Bush, Jr. – each in their day and in part contrary to their senior military advisors’ preferences – consciously opened two-front wars with disastrous consequences, the lessons of a now distant and largely forgotten economic collapse were quickly and painfully relearned. Mission accomplished.

The Volcker Rule –

For the financial sector, one of the most significant aspects of the Dodd-Frank Act is Title VI, known as The Volcker Rule. It is an often repeated misconception that The Volcker Rule simply rolls back the GLBA’s repeal of Glass-Steagall in 1999. This is not the case.

But The Volcker Rule reasserts regulatory control over how and the extent to which deposit-accepting commercial banks may engage in proprietary trading. To be sure, there are other important aspects of this legislation, such as controls over the extent to which a commercial bank can take an ownership interest in hedge funds or private equity funds – ensuring that a commercial bank couldn’t simply outsource its way around Volcker.

Perhaps surprisingly, the guiding principle of The Volcker Rule was not considered sufficiently pressing to be included in early drafts of the Dodd-Frank omnibus legislation. Revival of the initiative to restrict commercial banks from most aspects of investment banking was due almost exclusively to the personality and persistence of Paul Volcker, a venerable former Federal Reserve Chairman and leader of a prestigious international think-tank of elder banker-statesmen known as The Group of Thirty.

The Volcker Rule became relevant primarily as a bargaining chip during the course of tripartite negotiations among the respective House and Senate drafting committees and The White House, as the Dodd-Frank legislative structure grew & evolved. (A detailed account of this process can be found in Robert Kaiser’s authoritative ‘Act of Congress,’ Alfred A. Knopf, 2013.) As such, it gained momentum and finally the personal support of President Obama.

Too Many Architects –

The Volcker Rule’s perceived shortcomings and deficiencies stem primarily from a structural weakness built into Dodd-Frank’s architecture. There is little dispute that Dodd-Frank was hastily drafted and enacted – with many placeholders left to the regulators to sort through. Imagine someone who is extremely wealthy sketching out his or her dream home on the back of an envelope and placing it before a master architect: ‘Here, build me something that looks like this.’

Next, let’s imagine five architects – with their egos badly bruised from recent public allegations of laziness and incompetence – vying for the attention and affections of this wealthy client. It would come as no surprise that a five-way turf war would ensue. The dynamics would be such that specific decisions are proposed and taken not for the general good, but for each to show that he or she is superior to their colleagues.

Three architects – The Federal Reserve, Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. (FDIC), and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) – adopted a less aggressive, more consensus-oriented posture. But the two remaining architects – The Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) – chose a winner-takes-all approach. For these two, the coins of the realm are posturing and brinksmanship.

In this environment, opportunities for disagreement multiply as the pressure to meet deadlines builds. The greatest single object of this tug-of-war mentality has been the explicit exceptions to the Volcker Rule’s core principle: barring deposit-accepting commercial banks from engaging in proprietary trading. Volcker acknowledges three broad exceptions: (1) taking proprietary positions in executing client orders; (2) acting as a market maker; and (3) hedging.

While clever investment bankers can be expected to explore any cracks or fissures in a regulatory wall aggressively, the first two exceptions don’t offer much encouragement. (But hold that thought.) The really exciting opportunity for bureaucratic elbow fighting is the third category. What is hedging, after all, if not proprietary trading?

Hedging? Who, me?

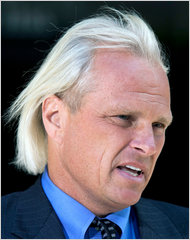

The CFTC – particularly Bart Chillton, the Commission’s most flamboyantly coiffed commissioner – has taken an ‘enumerated’ view – i.e., the regulator should issue a finite list of permissible hedging activity. If a commercial bank’s proposed hedging activity can’t be found on the list, then it is prohibited.

The banking industry has consistently supported a countervailing argument: Hedging is a crucial tool for maintaining a bank’s solvency and remaining competitive with foreign banks. This view has supporters in the academic community. Anil K. Kashyap, Professor of Economics & Finance at The University of Chicago argues that ‘The Volcker rule, if actually implemented in a strong form, could be very costly if it destroys the ability for banks to hedge.’ The SEC initially supported this view, but eventually relented to pressure from the CFTC and others.

Reliable business media are now reporting that Kara Stein, a Democrat on the SEC, has joined forces with CFTC Chairman Gary Gensler to require that the scope of acceptable hedging per this exception be narrowed even further. Their argument is that the hedging exception, as currently defined, would not have prevented trades similar to those engaged in by JPMorgan’s now notorious London ‘Whale’ trader.

But because of a White House-imposed deadline for completion of regulatory work on Volcker by year-end, this most recent change in approach takes on additional urgency. The Obama Administration is pushing regulators to come to closure on articulating Volcker’s contours soon because it is scheduled to take effect in July 2014, and additional delays would likely result in further slippage to the take-effect date.

Preparing for the Unknown –

Anticipating a maximally restrictive interpretation, several global investment banks are already scaling back their proprietary trading operations and/or shutting down their private equity units. Even though the Volcker Rule, as part of Dodd-Frank, was enacted into law three years ago, we are only now beginning to understand how it will be applied.

*The author’s views and opinions are entirely his or her own and may not reflect the views and opinions of 360factors.

Request a Demo

Complete the form below and our business team will be in touch to schedule a product demo.

By clicking ‘SUBMIT’ you agree to our Privacy Policy.